Athlete’s presenting with swimmer’s shoulder normally report pain in the subacromial region. These symptoms may be associated with a range of pathology such a bursitis, capsulitis or tendinopathy. Diagnosis may guide medical treatment such as pharmacological intervention with oral medication or injections, however the multi-factorial nature of shoulder pain and the limited specificity/sensitivity of shoulder assessment makes diagnosis problematic. As such it may be more beneficial to focus on the impairments that are associated with the onset of symptoms (as introduced in the previous blog).

Most swimmers’ will report an insidious onset of pain and can not identify a single specific event that has caused their symptoms. The subjective is paramount in identifying contributing factors e.g. alterations in training type and load, while the physical examination can help identify the relevance of biomechanical impairments.

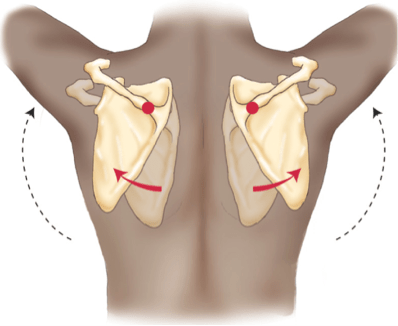

As discussed in the previous blog, Swimmers’ reporting sub-acromial pain often display, a forward head and rounded shoulder posture. This posture is associated with increased thoracic kyphosis, decreased cervical lordosis, protracted scapulae, and internally rotated/anterior humeral head. Soft tissue findings associated with this posture include restricted anterior shoulder musculature, lengthened and weak medial scapular stabilizers, tight glenohumeral posterior capsule, and weak anterior cervical flexors.

Physiotherapy, rehabilitation and strength & conditioning should focus on the demands of the sport (see previous blog) in the context of the presenting athlete. In an athlete presenting with symptoms modification of training type, volume or intensity may be required. Simply removing a particularly provocative S&C exercise may be sufficient to reduce symptoms enough for the swimmer to continue with their normal pool training load. However it is likely that some reduction in load either through volume or intensity will be required in the interim to allow symptoms to settle and to allow a shift in focus to shoulder strengthening and posture re-training.

Postural impairments can be managed through a range of techniques including, soft tissue release of the anterior musculature, mobilisations of the glenohumeral joint and strengthening of scapular retractors and cervical stabilisers

Soft tissue release of the anterior musculature, most notably pectoralis minor can be useful in reducing muscle tone and reducing the anterior drawer on the humeral head.

It is useful to teach athlete’s to self-manage this through Trigger Point release and self-stretching.

Posterior Capsule Mobility can be increased via posterior capsule mobilisation in supine and self stretch techniques such as the sleeper stretch. Care must be taken with the sleeper stretch as there is an opportunity for it to generate an increase in compressive symptoms if not undertaken with care.

The role of the rotator cuff is paramount in preventing humeral head migration. The rotator cuff originates from the scapula and as such the scapula plays an important role in defining the length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff (Kibler, 1998). As discussed previously, swimmers’ with shoulder pain often display reduced activity in the muscles that stabilise the scapula e.g. serratus anterior, rhomboids and lower trapezius.

Mosely et al (1992) undertook a piece of research to assess the effectiveness of different prone exercises in recruiting the scapula stabilisers. Prone exercises are particularly favourable as they can potentially mimic common swimming positions. The results are summarised below:

These results can help assist in choosing appropriate exercise that focus on increasing the endurance of the serratus anterior, lower trapezius, and subscapularis muscles. The four most widely used exercises supported both in research and clinical experiences are scapular elevation (scaption), push-ups with a plus, rowing, and press-ups. Some of these exercises may already be in a swimmer’s dry land programme and as such it is important to check technique and prescription. In my experience it works well to work to fatigue with these exercises, repeating 3-4 sets of each exercise per session. Given the high volume of pool based training these athlete’s undertake, it is useful to carry out these exercises after swimming or as an isolated workout session in order to minimise the effect on the swimming training. It is also worth bearing in mind that strength gains will be mitigated by cardiovascular training and as such 12-24 hours between pool and land training will contribute to more strength gains in a strength focused rehab.

Whilst there is a strong focus on scapular stabilisation within these 4 exercises, they also contribute to development rotator cuff strength-endurance. The prone scaption exercise for example (Y shape) as well as targeting the middle and lower trapezius fibres will also challenge the suprapsinatus (a key muscle in maintaining humeral head position). Whilst many practitioners will focus on attempting to isolate the rotator cuff with theraband exercises, I believe it is also useful to build in more functional complex movements that challenge the rotator cuff such as the military press, lat raises, lat pull downs and bent over rows.

Whilst many swimmers should be incorporating a dryland training it is valuable to liaise with coaches and the athlete to ascertain the content. There should be a focus on trubnk stability and strength endurance with an emphasis on pelvic positioning. Achieving a neutral pelvis and avoiding avoid excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis is a key teaching point. Exercises that focus on improving dissociation of the trunk on the pelvis and the pelvis on the hips are fundamental. Common exercises to assist in the process are dynamic plank variations, mountain climbers, swiss ball exercises, deadbugs, bridging varitations and greyhounds.

Periodisation of rehabilitation with training

Swimmers are reluctant to remove themselves from pool training as such it is likely that you will need to advise on the adaptation of training schedules and techniques in order to allow the athlete to continue to swim to some degree but also achieve the desired rest and/or adaptation required from rehabilitation. Modyfing a swimmer’s training will likely gain increased compliance with rehab than completing removing pool based training altogether. In some cases it may be necessary to remove the athlete from the pool altogether for a short period-although this is very rare in my experience. Ultimately time spent out of the water should be minimised and adjustments should be made to maintain as much pool training as possible, e.g.

- Temporary reduction in training volume/frequency

- Avoid the use of hand paddles and kickboards which increase load/leverage

- Use swim fins to enhance the propulsion from the legs and reduce the stress on the shoulder

- Alter training patterns so that different strokes are used more frequently throughout the practice.

Further reading:

Kibler B. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:325–339.

Mosely JB, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J, Tibone J. EMG analysis of the scapular muscles during a shoulder rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:128-134.

Scovazzo ML, Browne A, Pink M, et al: The painful shoulder during freestyle

swimming: an electromyographic and cinematographic analysis of twelve

muscles. Am J Sports Med 1991;19(6):577-582

You can try this now, simply try and hold your shoulder blades together and raise your arms, then do the same while relaxed and letting your shoulder blades move. Which is easier?

You can try this now, simply try and hold your shoulder blades together and raise your arms, then do the same while relaxed and letting your shoulder blades move. Which is easier?